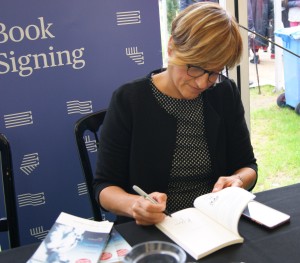

Our intern Ann had the pleasure of interviewing Karmele Jaio, a Basque writer whose novel Her Mother’s Hands (translated by Kristin Addis) was published recently by Parthian Books. They talked of the central themes of the novel, as well as the experience of being a Basque writer and of being translated.

Ann: What inspired you to write Her Mother’s hands?

Karmele: When I begin to write a book I never know exactly what I’m going to write about, but always feel that I have something inside that I have to write about, that I have something to discover there. Sometimes I think that I write to know what’s in my mind, to know what I want to say. When I began this novel I only had one picture, one image, in my mind: the hands of a woman on the sheet of a hospital bed, and a young woman sitting in a chair near her, looking at her hands. In that moment I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to say, but then I discovered that there were a lot of feelings inside me that needed to get out. I discovered years later that one of the inspirations of this book was the real worry that I felt at that time (without being conscious of it myself) because of seeing my mother converted into an old woman from one day to the next. I wasn’t conscious of this worry when I began to write the book. The writing of the novel helped me discover it.

A: What do you think was the most difficult part about writing Her Mother’s Hands and having it translated?

K: One of the worries that was present all the time while writing the book was not to be too dramatic. The situation I was describing was quite dramatic, so I was conscious that it was very easy to slide in a waterfall of drama. So I can say that I wrote the book with containment in that sense. And about the translations (I translated it myself into Spanish) the most difficult thing was not to lose the sound, the voice. Translating myself was a very difficult task, but also very enriching. I need to translate my own works, whenever I can, because Basque is a very different language. Basque is an isolated language; it has no connection to any other language. So, It’s very different from Indo-European languages. So when I translate into Spanish I need to rewrite my work. It doesn’t work if I translate very literally. More than ‘translate’ I say to myself: how would you write this in Spanish? And I write it that way, because I write in a very different way when I write in Basque than in Spanish. Each language takes you on a different path. And translating your texts is a very good exercise as it makes you know your style of writing better. While I’m translating my own work, I feel like I’m seeing what I wrote in Basque in front of a mirror. I see details of my way of writing that I didn’t know. It’s a hard but a very enriching exercise.

A: How does it feel to have your book translated?

K: Basque is a minority language. When we write in Basque we know that we are writing for a small community of readers. So translation is, obviously, important for us. For Basque literature and for Basque writers it is very important to be translated. So I feel very fortunate because more readers can understand the novel now. This moment right now is a very important moment to Basque Literature. Basque is an old language, but it is at the same time a very young language. In the 1970s, the Basque language was unified, was standardised. So, at that time a new standard language was created called euskara batua. And we write in this language. So Basque writers now feel like treading on new ground, treading on freshly fallen snow. We do not have that huge literary tradition of other languages and this gives us also some kind of freedom when we write.

A: This isn’t your first published work. How does it feel to have everyone treat you as if this is your first book?

K: Her Mother’s Hands was my second book and my first novel, written some years ago. After writing it, I have written another four books, but this is still the most well-known. I understand that is the first time that it appears in English so for English readers it is like my first book. It’s like beginning again. I know the route of this book in Basque (it was very good, better that I expected) but I do not know it in English. It would be very great news if the welcome of the English version was as good as it was for the Basque one.

A: Her Mother’s Hands is the first of your works to be available in English. Could you tell us a little about your other works? Anything you are particularly proud of?

K: Her Mother’s Hands is my most well-known book, but like I said, I wrote another five books: another novel, three short story collections and a poetry book. I always say that I’m a better writer of short stories than novels. I love the power of suggesting that the short stories have. I think I give the best of me in the short stories. And also I am satisfied with my poems.

A: Nerea is a journalist like yourself. How much of her work life is based on your own experiences?

K: I chose this job for Nerea because I thought that it was going to be easier for me to talk about a job I know. That’s the main reason. At the same time, I liked to talk about the representation of reality. Newspapers are doing a representation of reality every day, and we read news like they were reality itself. They are a representation, not the truth.

A: Did you have any particular influences (other books, media or authors for example) in your writing of Her Mother’s Hands or in your authorship in general?

K: Most of my influences are short story writers. I learned to write by reading short stories (Carson McCullers, Katherine Mansfield, Julio Cortázar, Raymond Carver, John Cheever, Dorothy Parker…), and in the last couple years my favourite writers are also short story writers like Alice Munro. I love her writing.

A: The book has a lot of very spirited and central female characters. Did you make any conscious choices in regards to the women in your book?

K: It wasn’t a conscious choice. The women appeared there. I think one of the reasons for this is because I’m writing about caring people, and, as we all know, caring is still in this world mostly in women’s hands.

A: At your talk at the Edinburgh International Book Festival you said that you wanted to write about relationships and their development. Would you like to elaborate a little on this?

K: In all of my books, there always appears one central theme: the difficulties of communication between people. If I had to describe the world I write in, I would say that it is the world of unspoken words. For me, in all these books it is of more interest what the characters don’t say than what they say. I think that is like real life: we talk about trivial things, and we hide our more important worries inside. For me writing is discovering, and I discovered that the communication between people is one of my worries. I think that we can live with one person for years and still be two strangers.

A: The book has a particular focus on the power and lure of the sea. Is that something that you have felt yourself?

K: Yes. My family is from the coast, from a little village called Lekeitio. My parents had to leave the village and go to a city, Vitoria, in the central part of the country because of my father’s job, and I always listen to my mother saying that in the city she felt that she couldn’t breathe – she needed the sea. And for me the sea has always had this connotation of freedom. In the novel, the sea is a metaphor of life, sometimes it is calm and sometimes it’s furious, but it’s important to look at it with a raised head, with one’s chin up as Nerea’s mother says.

A: How much do you think the uniqueness of Basque experiences (of nationhood and language or lack thereof?) has influenced your writing?

K: I think that we always write from our nearest experiences, and these experiences, of course, are modelling our writing. The only way to talk about a universal theme is to talk about a very concrete thing that you know and that you live. So, I write from my nearest reality and at the same time I think I am writing a universal story that anyone, in other places, can understand and feel.

The language is also very important to me at this point, because writing in a minority language is always a choice. All Basque writers are bilingual, all of us, so first, we have to decide in which language we are going to write. A French or an English writer maybe doesn’t have to think about that. And this choice also has an influence on the way we write.

Karmele Jaio Eiguren (1970-)

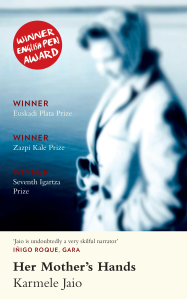

Karmele Jaio is a Basque journalist and writer. She has published several novels as well as short story and poetry collections. Her Mother’s Hands is one of the best selling Basque novels in recent years. It was first published as Amaren Eskuak in 2006 and subsequently translated into Spanish. It has received the PEN Translates Award, and has won the Igartza Prize. In 2013 it was made into a film, which was presented at the San Sebastian Film Festival. One of her short stories appeared in the anthology Best European Fiction 2017.

If you would like to know more about Her Mother’s Hands, you might want to read Ann’s review of it here on the blog.

One thought on “Interview with Karmele Jaio”